Rabbi Leon A. Morris

Published in the summer of 2013 in CCAR Journal: The Reform Jewish Quarterly. See here for a PDF of the article.

The notion of sacrificial offerings was an anathema in the shaping of a modern Jewish life. Since the earliest days of Reform Judaism, those most ancient forms of divine service were understood as primitive and outmoded. Although the classic, traditional liturgy continued to reference the ancient sacrificial service that predated it, the very first nineteenth-century liturgical reforms removed most of the references to the Temple, and to the sacrifices that had been offered there.

There are many examples of this in both Reform liturgy and ritual. The wording for Birkat Avodah (r’tzei Adonai Eloheinu), the seventeenth blessing of the Amidah on weekdays, and the fifth blessing of the Shabbat and festival Amidah, was altered to remove the references to sacrificial offerings. Musaf, a service specifically recalling the additional sacrifice on Shabbat and festivals, was either altered or eliminated altogether. The maftir reading for special Sabbaths, particularly those that recalled the specific offerings of that festival day, were eliminated.4 The Torah reading for Yom Kippur morning from Leviticus 16, describing the sacrificial service to be performed by Aaron and his sons—the original observance of Yom Kippur—was also eliminated and a different selection was chosen. Likewise, the most distinctive liturgical rubric of the classic Yom Kippur liturgy, Seder HaAvodah was either radically altered or excised altogether. Even the piyut Ein Keloheinu had the final line excised in order to avoid referencing that “our ancestors offered fragrant incense.”

This deliberate distancing from the sacrificial service, and from memories of the ancient Temple, extended well beyond the prayer book into daily ritual life. The washing of the hands prior to eating bread with its accompanying blessing recalls the priests who washed prior to eating from the sacrifices. This practice was by and large eliminated. Similarly, the salting of bread recalling the salting of the sacrifices was no longer encouraged. These reforms extended to the Hebrew calendar itself. Tishah B’Av, the anniversary of the Temples’ destructions, has generally not been marked in the majority of Reform congregations, and even the newest American Reform prayer book has no liturgy to mark the day.

To the sensibilities of modern Jews attempting to shape a nineteenth- and twentieth-century Judaism, the primitive nature of animal and grain sacrifices seemed to offer little by way of inspiration or critical ideas. The burning of animals in service to God seemed cruel. The idea that God was to be found in one central place, and the land of Israel in particular, was highly objectionable to Jews eager to demonstrate their loyalty to the countries in which they lived.

What was to be gained by this elimination of references to the sacrificial service? The most prevalent justification is rooted in a rejection of the hope for the rebuilding of the Temple and the reestablishment of sacrifice. In fact, many of the early Reformers seemed to assume a necessary and inseparable connection between referencing the centrality of sacrifices in our past and the undying hope for the Temple to be rebuilt and for sacrifices to be restored in our future.

The linking of those two ideas has continued to our time. For example, in an article almost a decade ago in this journal about the centrality of the Avodah service, Herbert Bronstein writes:

The elimination of the Musaf service from Reform Jewish worship as early as the late nineteenth century is, of course, understandable in the light of Reform’s constant and consistent opposition, from its beginnings, to prayers for the future restoration of the priestly sacrificial cult of the Jerusalem Temple.

Does such a link have to be made at all? Certainly, there could be a recollection of the central role that sacrifices played in the past without any hope for their future restoration.

Indeed, even if deemed desirable, it would be impossible to entirely eliminate the memory of sacrifice from contemporary Jewish life. References to the Temple and to sacrifice are unavoidable in classical Jewish sources. Indeed, they are ubiquitous as a refer- ence point, as metaphor, and as symbol. Specifically with regard to prayer, references to sacrifices are indispensable. The sacrificial offerings are the very basis for our having morning and afternoon services. The names of the services themselves bear the name of those daily sacrifices.

The early Reformers assumed that what was most needed for a meaningful and relevant Jewish life was a severing of the connection between prayer and sacrifice. However, severing the link between prayer and the sacrificial system may have sub- verted that goal. More was lost from dropping the connection between them than was gained. There is much to be learned from the sacrificial system that has the potential of deepening our experience of prayer. These ancient practices present notions of relationship, closeness and distance, gift giving, and mystery. Our age opens us up to new possibilities of meaning that such connections can provide for us. Texts about the ancient sacrifices call upon us to develop approaches and methods of interpretation that can treat such texts seriously. To do so, we need to more clearly understand the relationship between sacrifice and prayer.

Sacrifice, Study, and Prayer: Replacement or Substitution?

Once the Temple was destroyed, and sacrifice was no longer being performed, an expanded notion of the sacred space and sacred service was required. Upon resolving to build the Temple, Solomon sent a message to King Huram of Tyre requesting wood and additional craftsmen. He writes:

See, I intend to build a House for the name of the Eternal my God; I will dedicate it to God for making incense offering of sweet spices in God’s honor, for the regular rows of bread, and for the morning and evening burnt offerings on Sabbaths, new moons, and festivals, as is Israel’s duty forever. (II Chron. 2:3)

Nothing lasts forever; not the Temple, nor its offerings. The Rabbis, living in the aftermath of the Temple’s destruction, are faced with the challenge of explaining what is meant by “Israel’s duty forever.” This interpretive and symbolic challenge is expressed in BT M’nachot 110a:

Rav Gidel said in the name of Rav: This refers to the altar built [in heaven], and Michael, the great ministering angel stands and offers a sacrifice upon it. Rabbi Yochanan said: These are the students who engage in studying the laws of sacrifice. The verse regards them as though the Temple were built in their days.

In many ways, the disagreement between Rav Gidel and Rabbi Yochanan is about what constitutes avodah (the sacrificial service) in their day, and by extension, in ours.

Rav Gidel posits a “virtual” temple in heaven in which the ancient rites of the Temple continue unabated. In contrast, Rabbi Yochanan claims that the very meaning of avodah has changed in the aftermath of the Temple’s destruction. The place of avodah has shifted from the Beit HaMikdash (Temple) to the beit hamidrash (study hall). All post-exilic Jewish communities, both Orthodox and Reform, are in many ways an extension of Rabbi Yochanan’s reasoning. The form of divine service has changed.

Rabbi Yochanan’s boldly adaptive interpretation is representative of the Rabbinic project in which the human-God encounter shifts from the Temple to the study hall. Sacrifice lived on, not as performance but rather in memory, language, and imagination. Study is redefined as a religious act, not simply learning in order to do, but as a performance itself.

Following the debate between Rav Gidel and Rabbi Yochanan, on the very same Talmudic page we read the opinions of Rava, Resh Lakish, and Rabbi Yitzchak. Their voices cover a spectrum of opinions regarding the relationship between study and sacrifice.

Resh Lakish said: What is meant by the verse, “This is the teaching [Torat] of the burnt offering, the meal offering, the sin offering, the guilt offering . . .”? (Leviticus 7:37) Anyone who engages in [the study of] Torah, it is as though they sacrificed a burnt offering, a meal offering, a sin offering and a guilt offering. Rava [objected] saying: This [verse] says for the burnt offering, for the meal offering. [According to Resh Lakish’s opinion] it should have said the burnt offering and the meal offering . . . Rava said: Anyone who engages in [the study of] Torah does not need a burnt offering, nor a meal offering, nor a sin offering, nor a guilt offering. [The repetitive use of the prefix lamed here is interpreted as meaning lo, “no.”]

Rabbi Yitzchak said: Why is it written, “This is the teaching [Torat] of the burnt offering, the meal offering, the sin offering, the guilt offering . . .”? [In order to teach that] anyone who engages in the study of the sin offering is regarded as though he sacrificed a sin offering; anyone who engages in the study of the guilt offering is regarded as though he sacrificed a guilt offering. (M’nachot 110a)

On one end of the spectrum, Rabbi Yitzchak suggests that study of a particular type of sacrifice is the equivalent of offering that specific sacrifice. For him, study and sacrifice are most closely linked when study parallels the sacrifices for which it serves as a substi- tute. On the other end of the spectrum, Rava suggests that there is no need to measure study against sacrifice—ours is a whole new world, and the study of Torah, regardless of its subject, replaces sacrifices and precludes a need for engaging with the memory of the sacrificial system at all.

While this particular sugya deals with the relationship between sacrifice and study, it nonetheless presents us with two conceptual frameworks that are equally helpful to us as we consider the relationship between sacrifice and prayer: prayer as replacement for sacrifice and prayer as substitution for sacrifice.

By replacement, I mean to suggest that prayer or study obviates the need for sacrifice and takes on the same value sacrifice once had. This replacement model completely severs the connection between sacrifice and prayer. Like Rava’s position above, prayer in itself replaces sacrifices and is not reliant upon liturgical recollec- tions of the sacrificial system.

One Talmudic example of this approach might be found in the rhetorical question posed in Taanit 2a, “What is the avodah of the heart?”![]()

Drawing upon the words of the Sh’ma’s second paragraph, “If, then, you obey the commandments that I enjoin upon you this day, loving the Lord your God and serving Him with all your heart . . .” (Deut. 11:13) the Talmud states that it is prayer that is now the service of heart. In contrast, by substitution I mean to suggest that prayer or study evokes the sacrifices themselves and reminds us that these words recall and represent the sacrificial service that can no longer be performed. These prayers or study texts serve as substitutes for the sacrifices themselves. This approach is demonstrated in BT B’rachot 26b:

It has been taught also in accordance with R. Joshua b. Levi: Why did they say that the morning Tefillah could be said till midday? Because the regular morning sacrifice could be brought up to midday. R. Judah, however, says that it may be said up to the fourth hour because the regular morning sacrifice may be brought up to the fourth hour. And why did they say that the afternoon Tefillah can be said up to the evening? Because the regular afternoon offering can be brought up to the evening.

When trying to delineate Rabbinic sources about prayer and sacrifice along this conceptual framework of replacement and substitution there is a great deal of ambiguity. Indeed, this is the case with the Rabbinic interpretations of one of the most widely cited texts about the relationship between sacrifice and prayer, Hosea 14:3:

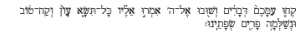

Take words with you and return to the Eternal. Say to God: For- give all guilt and accept what is good; we will pay the calves of our lips.

The end of this verse, un’shalmah farim sefateinu, which JPS translates as “instead of bulls, we will pay [the offering of] our lips,” notes that the meaning of Hebrew is uncertain. There are subtle differences in interpretation found in various midrashim that could be understood to be reflective of our conceptual framework—prayer as substitution or as replacement. In P’sikta D’Rav Kahana, Shuva 24, Rabbi Akiba asks, “Who pays for those calves that were offered before You? Our lips in the prayers that we pray before You.” ![]() The midrash asserts that our words

The midrash asserts that our words ![]() and prayers are the equivalent of our offerings of old. They are now the equivalent of the calves that had been offered. Alterna- tively, in Shir HaShirim Rabbah 4:9, the midrash states, “What shall we pay in place of the calves and in place of the scapegoat? Our lips.”

and prayers are the equivalent of our offerings of old. They are now the equivalent of the calves that had been offered. Alterna- tively, in Shir HaShirim Rabbah 4:9, the midrash states, “What shall we pay in place of the calves and in place of the scapegoat? Our lips.” ![]() Our words will serve as substitutions in place of the calves and other sacrifices that were once offered. They will be our offerings. In P’sikta D’Rav Kahana, our words are our offerings. They are a replacement. In Shir HaShirim Rabbah, our words are offered in place of those offerings. They are a substitution.

Our words will serve as substitutions in place of the calves and other sacrifices that were once offered. They will be our offerings. In P’sikta D’Rav Kahana, our words are our offerings. They are a replacement. In Shir HaShirim Rabbah, our words are offered in place of those offerings. They are a substitution.

The Musaf Model

Our early Reform heritage already presents us with some models of how this “substitution model” might take hold in a post-modern context. Jakob Petuchowski demonstrated the complex relationship that has existed with regard to the Musaf Service and Reform liturgies. While most of the European rituals retained some form of the Musaf Service, the liturgy needed to be adjusted to make it theologically in line with Reform sensibilities. Part of the compelling reasons to maintain it had to do with the fact that, as with many traditional congregations, a critical mass of the congregation does not attend the earlier part of the service.

As religious reform in Europe began to take on the forms of a movement, the discussion of how to treat Musaf arises. In the 1884 Frankfort conference, an appointed Commission on Liturgy found themselves unable to decide decisively on whether or not to retain the Musaf Service.

One of the supporters of retaining the Musaf Service with references to the sacrifices was Abraham Adler, whom Petuchowski notes was regarded as a “radical reformer.” Responding to the notion that the idea of sacrifice had become obsolete, Adler responds (as cited by Petuchowski),

The idea of sacrifice must be an eternally true one, since we can- not and must not assume that, throughout the millennia, Judaism has retained a lie. There is a confusion between the idea itself and the form in which that idea was outwardly expressed. The idea of sacrifice is one of devotion, of the union of the finite individual with the Infinite, the submersion of the transitory in the eternal Source. As long as man himself still stood on the level of externality, he was in need of the external act, through which alone he achieved self-consciousness . . . Only when Judaism transcended the level of externality, did sacrifice become something abstractly external, and only then did the Prophets begin to fulminate against it. The idea then created for itself a new and more appropriate form, that of prayer. In that sense we must understand the Talmudic passage, tephilloth keneged temidin tiqqenu (the sacrifices found their counterpart in the prayers).

Adler concludes with a statement that could serve as a basis for a twenty-first-century “substitution model” of prayers about sacrifice.

We cannot, therefore, become indifferent to the sacrificial cult, since, in it, we possess the original form of devotion. I, therefore, demand the retention of those liturgical passages which refer to the sacrificial cult—as a reminiscence. On the other hand, the prayers for its restoration, about which we cannot be serious, are to be omitted. (emphasis mine)

Petuchowski notes that Adler’s recommendations for liturgical practice were adopted.

Petuchowski shows how these various Reform Musaf liturgies shift from preserving a memory of the sacrifices to those that deliberately sever such connections. Early nineteenth-century Reform liturgies include a Musaf Service that is contextualized as a substitution for the sacrifices they recalled. This is reflected in Adler’s perspective above and became the prevalent approach to Musaf prayers. However, Geiger’s prayer book of 1870 includes Musaf but shapes the liturgy in ways that see it as a replacement. The Musaf Service continued to be included, but once the theoretical basis had been eliminated from the prayer itself, it was only a matter of time before Musaf itself would be eliminated.

Apart from Musaf, one can find in earlier Reform prayer books other examples of the “substitution model” at play. In Einhorn’s Olat Tamid, as in Gates of Repentance, a reference to the sacrificial element of Yom Kippur is unavoidable. Here we see ways in which the ancient rites can be unapologetically referenced and used as a metaphorical application to our own lives:

Like this priest of old, we, too are called to this duty; our priestly service demandeth that we, to the fullest extent of our ability and opportunity, bring the tidings of peace and reconciliation unto all. We, too, must lead back upon the right path those that have gone astray, and honor Thee by keeping alive and deepening the consciousness that all the children of Abraham are bound together by the ties of the common responsibility to sanctify Thy name in the eyes of the world.

Preserving the Power of the Sacrifice

In Reform liturgy, barring the exceptions noted above, we have almost entirely approached prayer as replacement for sacrifice rather than substitution. In doing so, the centrality of sacrifice has been muted and its memory deemed insignificant. In contrast, by embracing a model of substitution rather than replacement we open up a symbolic universe that greatly increases the significance of prayer.

The “post-modern turn” has renewed an interest in symbols and ritual. There is a greater openness toward the very experiences that were dismissed by previous generations as “primitive.” There is a recognition that reason is the not the sole criteria for determining what can have religious meaning for us:

Obviously modern Jews can do as they please with the prayer- book without fear of sanction, but it is important that, if they make any changes, they do so for reasons which are very good indeed. Simply to remove the sacrificial readings because of a conception of “higher” and “lower” religion, which will not stand the test of scrutiny, is an injustice not only to one generation but to the generations which are heir to the fruits of this misconception.

Approaching liturgy as a substitution for sacrifice, rather than a replacement, keeps the memory and symbolism of sacrifice alive. That memory and symbolism, in turn, expands the meaning and significance of our prayer life. The notion that prayer is avodah sh’balev (the sacrificial service of the heart) is only meaningful so far as one continues to understand what avodah itself once was. Once that connection is severed, the effect is a diminishment of the significance of prayer, a narrowing of the wide spectrum of meaning that prayer can have.

If a connection between sacrifice and prayer is maintained or reestablished, it offers vital ideas that can revive our spiritual lives. Prayer becomes an offering, a gift, something we deeply long to be received. The language of sacrifice in the context of prayer also reminds us that ours is a communal relationship with God, and that prayer too is not just about the individual, but about the collective. Furthermore, a connection between prayer and the ancient korbanot underscores the enormous gap that exists between ourselves and God, a needed counterpoint for us in a spiritual climate in which God is increasingly presented exclusively as “our friend” or “our conscience.” When we see our prayers as a substitution for sacrifice—on the Yamim Noraim and throughout the year—we assert that every home and every synagogue is a Temple, and that each Jew is a priest.

Once we construct prayer as a replacement, rather than as a substitution for sacrifice, we diminish our spiritual vocabulary, lose central frames of reference, and allow a locus of Jewish memory throughout the ages to disappear. Restoring this connection allows such words and memories to contribute a myriad of ideas we need in our prayer life now more than ever before.

Read the original Calves of Our Lips PDF here

Notes

1. Paragraph 5 of the Pittsburgh Platform states: “We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state.”

2. The traditional wording includes the words, “Restore the service to Your most holy House, and accept in love and favor the fire-offerings of Israel and their prayer.” Jonathan Sacks, The Koren Siddur (Jerusalem: Koren Publishing, 2009). Compare with Mishkan T’fi lah (and previous Reform prayer books), where the words v’hashev et haavodah lid’vir beitecha v’ishei Yisrael are omitted, but creatively, the words remaining are joined to make one coherent statement.

3. The diverse approaches to Musaf in Reform liturgies are explored below.

4. For example, Num. 28:9–15 for Shabbat Rosh Chodesh; Num. 29:1–6 for Rosh HaShanah morning; Num. 29:7–11 for Yom Kippur morning; Num. 29, selected verses for each day of Sukkot; Num. 28, selected verses for each day of Passover, and for Shavuot.

5. Union Prayer Book II and Gates of Repentance substitute selected verses from Parashat Nitzavim, Deut. 29:9–30:20.

6. For the absence of ritual hand-washing and salting of bread, see On the Doorposts of Your House (New York: CCAR, 2010), 62. In Gates of Shabbat (New York: CCAR, 1991), 28–29, although the ritual blessings are not included in the liturgy itself, both the mitzvah of hand-washing and the custom of salting bread are explained and presented as an option.

7. The only official American Reform liturgy exclusively for Tishah B’Av is the work of Herbert Bronstein, in The Five Scrolls (New York: CCAR, 1984). Gates of Prayer: The New Union Prayer Book (New York: CCAR, 1975) includes a liturgy that can be used interchangeably for Yom HaShoah or Tishah B’Av.

8. Herbert Bronstein, “Yom Kippur Worship: A Missing Center?” CCAR Journal (Summer 2004): 7–15.

9. See Moshe Halbertal, On Sacrifice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012).

10. Jakob Petuchowski, Prayerbook Reform in Europe: The Liturgy of European Liberal and Reform Judaism (New York: World Union for Progressive Judaism, 1968). See chapter 9, “Reform of the Musaph Service.”

11. Ibid., page 243-244. Petuchowski cites Protokolle und Aktenstrücke der zweiten Rabbiner-Versammlung, p. 382.

12. Ibid.

13. David Einhorn, Olat Tamid: Book of Prayers for Jewish Congregations (1913). “Services for the New Year’s Day and The Day of Atonement,” p. 185..

14. Richard Rubenstein, After Auschwitz: Radical Theology and Contemporary Judaism (New York: Macmillan, 1966), 108.