Leon A. Morris Apr 10, 2023 – Sources, Spring 2023.

From shrinking attendance at worship services and the merging and closing of congregations to a crisis of generating new clerical leadership, the decline of liberal religion is evident throughout Western Christianity and Judaism. Demographics cast doubt on the degree to which the extreme accommodation, flexibility, and individualism of liberal religiosity can also sustain deep commitments. By liberal Jews, I mean those who are drawn to a liberal—that is, not strictly halakhic—approach to Jewish life and observance, whether they affiliate with Reform, Reconstructionist, or independent congregations; or they belong to Conservative synagogues but do not share their movement’s commitment to halakhah; or they don’t affiliate at all, but still maintain a connection to observant Jewish life. While we liberal Jews may remain unable and rightfully unwilling to submit to the claims of classic or traditional religious authority, I believe we must nonetheless embrace notions of obligation and duty, and hold them dear alongside the much more frequently touted value of personal choice. The time has come to use our freedom to choose to feel commanded.

A helpful illustration of my argument emerges from distinctions between “surrender” and “submission” made by the psychoanalyst Emmanuel Ghent in an imaginative and influential article he published more than 30 years ago. Ghent defined surrender as “a quality of liberation and expansion of the self as a corollary to the letting down of defensive barriers.” Rather than abandoning or rejecting the self, surrender’s “ultimate direction is the discovery of one’s identity, one’s sense of self, one’s sense of wholeness, even one’s sense of unity with other living beings.”1

Ghent defines submission in sharp contrast to the notion of surrender. Submission allows a person to be controlled by another’s power while one’s own distinct sense of identity is weakened.While surrender is a powerful embrace of self, submission is self-negating. It is easy to confuse surrender with submission.In fact, Ghent defines masochism as distorting the human desire for surrender by finding it in submission, “the ever available lookalike to surrender.” What we really desire is to be able to surrender our lives to a larger force, not to be controlled by someone else.

When I look at liberal religion, and at my fellow liberal Jews in particular, I see that we may be guilty of a distortion in reverse.We look at the most halakhic and demanding forms of religious life and see in them a submission to authority and with it, a negation of the self. We imagine the haredi Jew who relies on the opinion of his or her rabbi for decisions about how to live, how to dress, and who to vote for, and out of our strong aversion and opposition to this form of submission, we have perhaps overcompensated, excising all aspects of surrender from our religious lives. In doing so, we have denied ourselves an essential human desire and lost access to a vital aspect of religious experience that would allow traditional forms of religious expression to be a persuasive and animating force in our lives.

In our affluent capitalist culture, choices proliferate in every area of life. Such choices—from where we live, to what car we drive, to how we spend our free time—provide us with meaning and self-definition. But in our religious lives, having endless options at our disposal is a mixed blessing. Flexibility and accommodation, qualities that exemplify liberal religion, can also become a refusal to surrender.The proliferation of Passover Seders held on the most convenient day in April rather than on the holiday’s first night, whenever it might fall in our work and social lives, is a well-documented example of this trend.

This emphasis on choice in liberal religious life results in an erosion of a sense of commitment and obligation, and by extension, our sense of who we are.As Antonio Martinez Garcia notes in his article, “Why Judaism?”:

The problem is that it’s the unchosen obligations—or the obligations chosen but whose downstream responsibilities cannot be unchosen—that will give us the only real meaning in life. Family, children, our hometowns, our childhoods, our ethnic identity (if we have one), or the chosen-but-undoable commitments—marriage, joining the military, that company we start, religious faith—are the defining obligations where our selves really play out.

Viewing the most meaningful parts of our lives as those for which we feel a strong sense of obligation can make us rethink the role of choice in religious life.And yet, choice and personal autonomy are inescapable parts of our lives. As Paul Mendes-Flohr put it three decades ago in his book, Divided Passions: Jewish Intellectuals and the Experience of Modernity,

We thus face a profound impasse.Modern individualism seems to be producing a way of life that is neither individually nor socially viable, yet a return to traditional forms would be to return to intolerable religious determinism and oppression. The question, then, is whether the old civic and biblical traditions have the capacity to reformulate themselves while simultaneously remaining faithful to their own deepest insights.

We cannot and are not willing to put the genie back in the bottle.Neither are we prepared to become fundamentalists.Nonetheless, we need to experience obligation, calling, and duty in more pronounced ways.

In light of our fear of submitting, how can we embrace surrender?

This question is even more pointed in this time of rising religious extremism, when the destructive and divisive effects of submission to authority are rampant, and amplified in each day’s newspaper.How do we liberal Jews shape a religious life that is engaged and disciplined, that is open to surrender, that allows us to experience a sense of wholeness and unity, and that takes us beyond ourselves?

This distinction between surrender and submission might be read into a well-known Talmudic story about the acceptance of Torah by the ancient Israelites:

The Torah says, “And Moses brought forth the people out of the camp to meet God; and they stood at the lowermost part of the mount” (Ex. 19:17). Rabbi Avdimi bar Hama bar Hasa said: “the Jewish people actually stood beneath the mountain, and the verse teaches that the Holy One, Blessed be He, overturned the mountain above the Jews like a tub, and said to them: ‘If you accept the Torah, excellent, and if not, there will be your burial.’” Rav Aha bar Ya’akov said: “From here there is a substantial caveat to the obligation to fulfill the Torah. The Jewish people can claim that they were coerced into accepting the Torah, and it is therefore not binding.” Rava said: “Even so, they again accepted it willingly in the time of Ahasuerus, as it is written: “The Jews ordained, and took upon them, and upon their seed, and upon all such as joined themselves unto them” (Est. 9:27),” and he taught: “The Jews ordained what they had already taken upon themselves through coercion at Sinai.” (bShabbat 88a)

According to this Talmudic aggadah, the covenant at Sinai was initially adopted under duress: with the mountain hanging above them, the Israelites feared death if they refused to accept.However, a contract adopted under this sort of pressure is invalid, leading Rav Aha bar Ya’akov to conclude that the people are not actually bound by the laws of Torah. He worries about the validity of the Sinaitic covenant because, to his mind, life is not worth living without Torah. Citing the book of Esther, however, Rava argues that when a later generation freely accepted the terms of the contract, they renewed the earlier commitment, eliminating any concern about coercion long before the rabbinic era.

This story hinges on the interplay between free will and obligation, between choice and acceptance.Is God’s wielding of Mount Sinai, of literally holding it over the Israelites’ heads, an experience of submission or of surrender? The story can be read either way. Those who see this as a moment of submission infer that acceptance of the covenant requires submitting to the demands of a God who threatens to crush us at any moment.This is the sort of reductionist reading that fundamentalism provides.

A more nuanced reading, however, is also possible, and it benefits fromGhent’s distinction between submission and surrender. He writes, “Acceptance can only happen with surrender…It is joyous in spirit and, like surrender, it happens; it cannot be made to happen.” From this perspective, the revelation at Sinai can be understood as a moment of truth and clarity for which acceptance is a forgone conclusion. The acceptance of Torah at Mount Sinai is surrender to the covenant and to life itself. This is how French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas understands this Talmudic passage when he writes, “the Jewish text starts in a non-freedom which, far from being slavery or childhood, is a beyond-freedom.” What might appear as the “non-freedom” of acceptance under coercion is actually a “beyond-freedom” that makes the decision of acceptance so overwhelmingly right, that our choice to say “I will do” feels as though there really was no choice at all.

This odd “beyond-freedom” acceptance of Torah undermines the sharp dichotomy between autonomy and heteronomy that was first explicated by Immanuel Kant in the late 18th century. In Kant’s definition, autonomy is a “property of the will by which it gives a law to itself.” That is, autonomy is the belief that the only laws that are just are those that are determined by the self. One example might be my own commitment not to steal, if I reach that commitment by thinking through why stealing is wrong on my own. In contrast, according to Kant, a law that comes from outside the self is heteronomy. Insofar as the mitzvot are commanded by God as expressed in the Torah, they fit into this category. Kant’s distinction between autonomy and heteronomy ultimately provided the foundations for modern conceptions of democracy, popular sovereignty, and freedom.It also played an important role in the development of modern Judaism and, in particular, in the emergence of a liberal Judaism that rejected halakhah as binding. Indeed, the preference for choice that we see among liberal Jews today assumes as stark a divide between autonomy and heteronomy as Kant did.

The German Jewish philosopher Franz Rosenzweig’s essay, “The Builders,” now a century old, stands as an important refusal of Kant’s dichotomy. Rosenzweig argues that religious decisions should be made not based on will, but on ability.As he writes,

We may do what is in our power to remove obstacles; we can and should make free our ability and power to act. But the last choice is not within our will; it is entrusted to our ability. It is true that ability means: not to be able to do otherwise—to be obliged to act. In our case, it is not up to an instinct, choosing by trial and error, to fight against the dangers of a return: our whole being is involved in it” (emphasis added).

Rosenzweig’s position is simultaneously liberal and conservative.He allows for individual and idiosyncratic paths in adopting and observing mitzvot, but,at the same time, he rejects personal will as a basis for navigating that path and insists that we do what we are able to do, not what we choose to do.

Rosenzweig’s contribution to the specifically Jewish discussion of autonomy and heteronomy is the distinction he makes between the notions of “law” (Gesetz) and “commandment” (Gebot) as two different ways of understanding a Jew’s relationship to mitzvot. As scholar Ephraim Meir writes, “Rosenzweig wanted to outline the conditions of living the Law today for his contemporaries. Gesetz, the objective Law, did not require mere submission, it was rooted in the divine imperative of love, the always-subjective and personal Gebot. Consequently, the Law was reinterpreted in a new way; it was a kind of ‘new Law’ not characterised by its coercive force, but rather by its possible subjectivisation.” 2

Rosenzweig articulated an embrace of mitzvot as commandments based on hearing in them a call from God. To fulfill the mitzvot as commandments is not just to obey as one does with the law, but to accept. As Rosenzweig writes, “the voice of the commandment causes the spark to leap from ‘I must’ to ‘I can.’ The Law is built on such commandments, and only on them.”

Rosenzweig’s distinction provides a model of how we might move beyond a dichotomy between autonomy and heteronomy today. But one need not rely on this early 20th century philosopher to conclude that Torah and mitzvot transcend the categories of autonomy and heteronomy. Rabbinic literature already alludes toelements of the nuanced ways that Rosenzweig describes the interplay between commandment and the self. For example, in the Rabbis’ reading of the Ten Commandments as described in the Torah, they offered a profound and bold reading of the law as “written in stone.”

“Engraved (harut) on the tablets.” What is the meaning of harut? This was discussed by Rabbi Judah, Rabbi Jeremiah, and the Sages. Rabbi Judah said: do not read it as “harut” (engraved), rather as “herut” (freedom) from captivity. Rabbi Nehemiah opined that it means free from the Angel of Death. The Sages were of the opinion that it means free from suffering. (Ex. Rabbah 41:7)

By playing with the vowels to change the Hebrew word harut into herut, that which at first appears as the polar opposite of freedom—the binding law engraved on the tablets—is seen anew as the basis of freedom. Commandment and freedom are not polarities. Rather, freedom expresses itself most fully through the opportunity to hear and live commandments.

A second midrash challenges the sharp dichotomy between autonomy and heteronomy by arguing that in fulfilling the mitzvot, we (alongside God) become the source of those commandments. Here, the rabbis comment on a verse from Leviticus:

“And you shall keep My commandments…and do them.’” (Lev. 26:3)Rabbi Hama said in the name of Rabbi Hanina: If you keep the Torah, behold you will be regarded as though you had made them [the commandments].(Lev. Rabbah 35)

Here, Torah transcends the relationship of God and human beings as commander and commanded, respectively.The human performance of mitzvot instead unites them, allowing us to be co-authors with God. In this understanding, mitzvot simultaneously have a heteronomous and an autonomous character.On the basis of this midrash, one might argue that the mitzvot are neither fully commanded by God, nor are they completely determined by us.

I see a parallel between the expansive self that emerges through surrender and the work of architects who must deal with parameters not of their choosing: the precise plot of a site, the building materials required by law, supply chain delays, and more. Within these limits—because of these limits—their creative ability grows, and as a result, they produce works of beauty and utility.

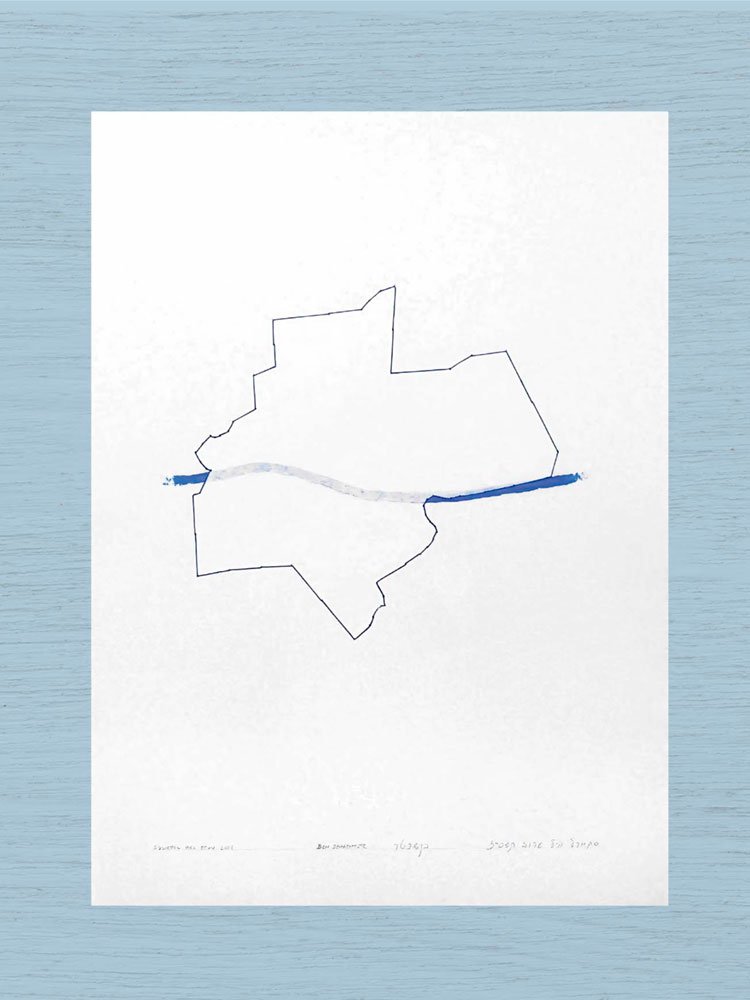

Not only architects, but arguably the work of all artists could be said to require surrender toboundaries, borders, and limits.These restraints can become a source of meaning and creativity.Consider, for example, the work of Ben Schachter, one of many artists to find beauty in the concept of eruv, the halakhic boundary that turns the public domain into a private one for purposes of carrying on the Sabbath. Schachter has created a series of portraits of actual eruvim around the world today.

Describing Schachter’s series, Richard McBee writes, “Schachter’s images are deceptively simple conceptual artworks.Each drawing is made of paint, graphite and thread on heavy watercolor paper.The images are of an unadorned outline in blue thread of the borders of a specific eruv in communities around the world.” In Schachter’s images, boundaries, borders, and limits become beautiful. They are the fuel for a creative and productive life.

In a post-modern embrace of surrender, what exactly would we liberal Jews be surrendering?In Ghent’s psychoanalytic terminology, we would be “letting down [our] defensive barriers.” We would be letting go of the defenses that make religious life bourgeois and formulaic, and we would be building communities in which we encourage and support one other as we turn mitzvot from laws into commandments.We would be helping one another to grow in Jewish deeds.We would be taking down the barriers that the precious gifts of reason and intellect have left in their wake.We would be opening ourselves to move beyond the critique modernity provides, by lifting up a hermeneutic of embrace to be held alongside our hermeneutic of suspicion.

By making such a choice, we would also be surrendering our time.Placing our lives within the rhythm of the Jewish calendar would mean that Shabbat and holidays are central in our lives.Time is indeed our most precious commodity.Each holiday carries with it concepts that are at the core of what it means to be a Jew.The family and the community come together to engage in a performative embrace of those ideas.

We would also be surrendering the illusion of an isolated human individualism, allowing our relationships with others and with the Other to become more central.The basis of these relationships is expressed through shared commitment and practice in a community that prays each day, that eats its meals in the sukkah (and invites others to do so), that takes the study of Torah seriously, that is present in times of sickness and in the shadow of death to provide help and support, no matter how inconvenient it might be.

This vision of a vibrant, robust liberal religious life may enjoin us to stop confusing surrender with submission and acceptance with obedience. Though fear of submission to God or to religious authorities is well-founded, we mustn’t deprive ourselves of shaping religious ways of life that enable us “to accept with our whole being, in joyous spirit.”

Endnotes