I have always been resistant to a Jewish identity primarily fueled by anti-Semitism. When the 2013 Pew Study of Jewish Americans found that remembering the Holocaust is the most central criteria of American Jewish identity, it filled me with deep sadness. 73% of American Jews list this as an “essential part of what it means to be Jewish”, even more than leading an ethical and moral life (69%) and working for justice and equality (56%). Other criteria like “caring about Israel” or observing Jewish law fall much further down on that list.

What it means to be a Jew, of course, is far too complicated for the average person being surveyed to articulate. Reducing the answers to survey categories and metrics doesn’t capture the full story. Still, what Pew revealed are the ways that tribal instincts predominate over deeper and thicker ways of identifying with Jewish life.

At times, it has even felt as though Jewish organizations rely on anti-Semitism and its perceived threat as a way of masking how otherwise disconnected and disinterested American Jews are about their Judaism. We have largely come to define ourselves instead by what others have done to us, especially in the last century.

For those of us on the front lines of Jewish education and community-building, such an approach to Jewish life seems to undermine a Jewishness that is rich in content and creativity. Passion and joy and connection are the foundations for a 21st century Jewish life, and not an emotional response to a never-dying hatred toward us. We want a Jewish life framed by Shabbat and festivals and not by Auschwitz. We seek a Jewish life that makes us sing and dance more than cry and mourn.

While Pew described the contours of a Jewish identity with little content built largely on the memory of marginalization and anti-Semitism, it turns out that the actual experience of anti-Semitism has often been a catalyst for stronger Jewish engagement. As Professor Michael Meyer wrote: “At times anti-Semitism has served to squeeze Jews back into the externally devalued group from which they were trying to escape, producing mild or severe rejections of self. But it has also had entirely the opposite effect, creating a renewed affirmation of Jewishness.”

Meyer describes that with the Nazi rise to power, some German Jews attempted to assimilate even more. However, “[t]he more common response was to look inward at a Jewish interior landscape that had long ago grown barren. Nazi anti-Semitism before the Holocaust thus had the general effect of restoring Jewish consciousness where it had eroded severely. The most assimilated of German Jews, often for the first time in their lives, now felt the need to confront and to reaffirm their Jewishness.”

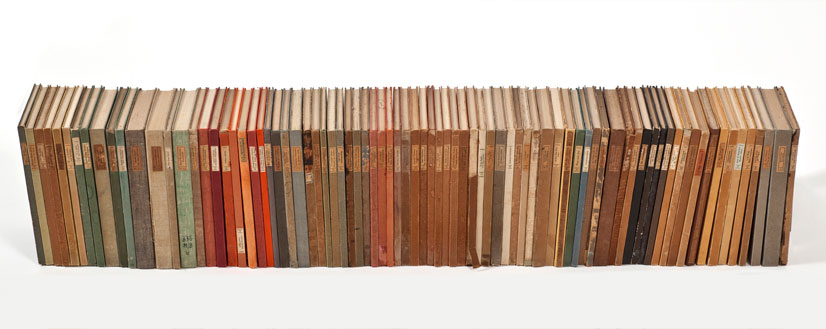

Last winter, as part of an exquisite exhibition on the Hebrew typeface at the Israel Museum, I encountered the Bucherei des Schocken Verlag (Library of the Schocken Verlag) for the first time. This series of books on Jewish life and literature, published in Germany from 1933 to 1939, was comprised of 83 slim volumes encompassing Bible, Rabbinic literature, medieval and modern poetry, history, mysticism, philosophy and more. The first volume, a translation of Isaiah’s prophecies of comfort by Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig was published six months after Nazi book burnings in Berlin. The last volume, Briefe by Hermann Cohen was printed in the late months of 1939.

This Schocken series made a deep impression on me, even more so as it was displayed in one of the rebuilt Jewish state’s most prominent cultural institutions. The series was created for the most intellectual, well-educated and highly assimilated Jewish community in the world subscribing to this bi-monthly arrival of the newest Jewish book by scholars who would become the preeminent minds in modern Judaism was an act of spiritual defiance. This renaissance of Jewish identity and Jewish learning in the face of unparalleled anti-Semitism is both inspiring and noteworthy.

America isn’t Germany in the 1930’s, and it never will be. But the sudden uptick in anti-Semitic incidents calls for responses that can themselves be redemptive. (While the main suspect in the bomb threats is one of our own, no arrests have been made in the three cemetery desecrations or in other incidents involving graffiti on Jewish sites and the dissemination of hate fliers.) In the face of hatred and disrespect, we can in turn embrace more fully who we are, as well as the texts and ideas that have sustained and nourished us through the ages.

In Anti-Semite and Jew, Jean-Paul Sartre writes, “Jewish authenticity consists in choosing oneself as a Jew — this is, in realizing one’s Jewish condition. The authentic Jew abandons the myth of the universal man; he knows himself and wills himself into history… he ceases to run away from himself and to be ashamed of his own kind… He knows that he is one who stands apart, untouchable, scorned, proscribed — and it is as such that he asserts his being… “

The American Jewish community has experienced ongoing confusion over the ways we can be simultaneously committed to a robust Jewish life without abandoning a concern for all people. How do we balance our Jewish particularism with our commitment to universalism? If the memory of anti-Semitism and its imagined threat has given rise to a Jewish identity largely lacking in content, we might ask ourselves whether actual anti-Semitism — for all that we do not want it and must fight it — can help us rediscover Jewish depth and meaning.

While common victimization does not, on its own, make for a lasting and viable Judaism, our natural survival-of-tribe instincts perhaps can lead us back to our texts and our ritual practices. We can see this moment in time as an opportunity to re-encounter the most meaningful aspects of our tribe. We can engage the cerebral cortex and not just the frontal lobe.

Rabbi Leon A. Morris is on the faculty of the Shalom Hartman Institute and Hebrew Union College. He is the incoming president of the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem.